![The benefits of managed portfolios [PODCAST]](/content/dam/thrivent/fp/fp-insights/advisors-market360-podcast/advisors-market360-podcast-16x9-branding-insights-card.jpg/_jcr_content/renditions/cq5dam.web.1280.1280.jpeg)

The benefits of managed portfolios [PODCAST]

Why they may be a good idea for clients and an even better idea for financial advisors.

Why they may be a good idea for clients and an even better idea for financial advisors.

02/27/2026

MARKET UPDATE

06/24/2025

With debt more than 100% of GDP and interest costs rising, many experts are saying the U.S. needs a long-term solution.

Treasury risk premiums are up, the probability of default has risen and the U.S. dollar has weakened.

If confidence continues to erode, bond markets could demand higher yields, prompting the government to act.

Financial markets across the world are paying more attention to the U.S. government’s growing debt burden. Whether it is the annual budget deficit (recently between -6% to -7%), total debt as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP, near 100% and rising) or the startling amount of total debt owed (currently about $40 trillion), all are high enough figures to raise concern. As the proposed tax bill is working its way through Congress, it is likely to add more borrowing, and tariff policy has raised questions about the outlook for domestic growth and inflation. As a result, financial markets are increasingly questioning the sustainability of the government’s approach to debt.

The U.S. has long benefited from its status as the world’s largest economy and a safer home for investment. U.S. Treasury bonds have been generally regarded as “risk free” and thus serve as the global benchmark for interest rates. Government, corporate, mortgage, credit card and other borrowing is typically calculated as a spread over a similar maturity U.S. Treasury security. And the U.S. dollar is the preeminent reserve currency—the currency that much of the world keeps its reserve cash in.

But Moody’s Corporation recently joined its fellow rating agencies S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings in downgrading the U.S. government’s credit rating from Aaa (the highest rating issued) to Aa1. The reasons were concerns that rising debt and sustained fiscal deficits could lead to higher borrowing costs which in turn could worsen deficits, fueling a vicious cycle that could ultimately have a quantifiable impact on the country’s credit risk profile and cost of borrowing.

Markets, however, were relatively unphased by the announcement, largely because it was the last of the major rating agencies to announce the change. That the U.S. government is no longer seen as a AAA credit from any of the three major rating agencies may prove to be a blip in its long-run history, but recent market dynamics are confirming that concerns about U.S. debt are growing.

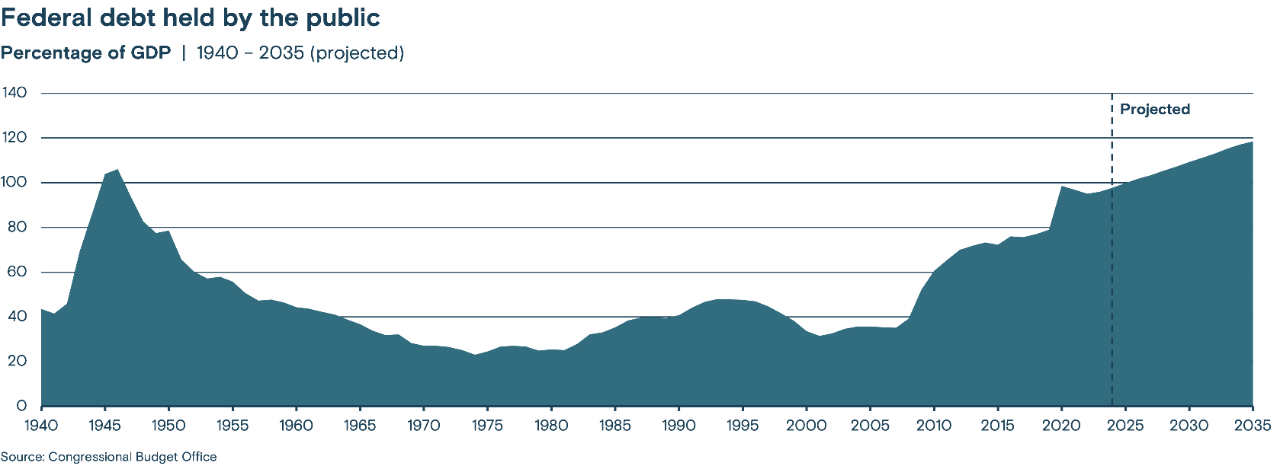

Total U.S. government debt as a percentage of GDP, a broad measure of the economy, has been rising rapidly since the turn of the century. As the figure below shows, it has more than tripled in just the last 25 years. While still shy of the all-time highs of the last century when it reached nearly 110% of GDP (a result of heavy borrowing to finance World War II), a range of projections suggest it will exceed that historical high within the next decade.

While there have been extenuating circumstances, such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC) that prompted a spike in total debt as a percentage of GDP, U.S. debt levels have consistently risen over the past 20 or so years. While overspending was often moderate, with annual deficits near 2-3% of GDP, the GFC resulted in a few years with deficits exceeding 8%, and COVID-19 resulted in two consecutive years where the deficit was greater than 12% of GDP.

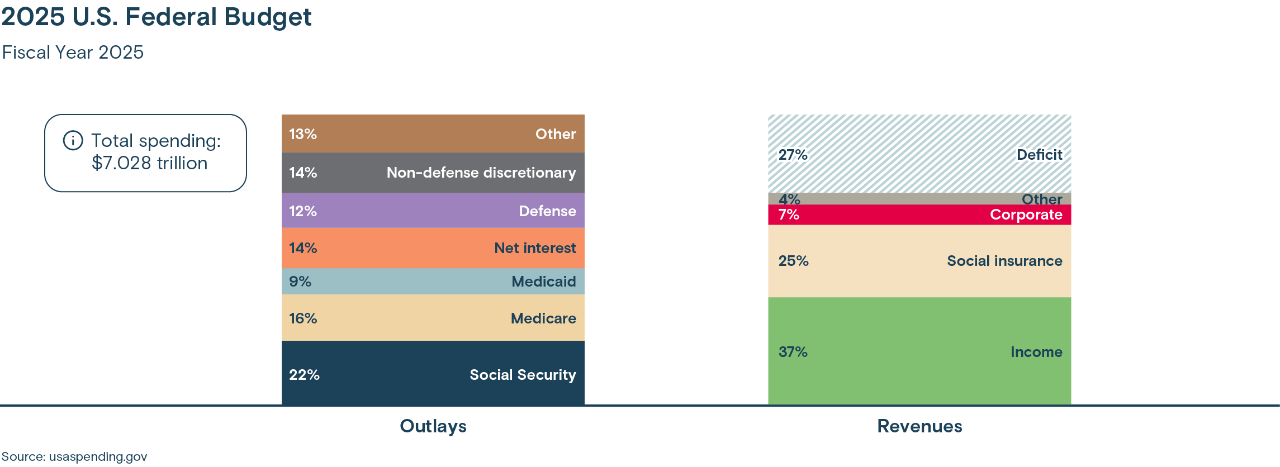

Today, the interest costs on the outstanding debt are more than $1 trillion per year, or more than 3% of GDP (double what it was in 2019 before surging inflation prompted sharply higher interest rates). To put that $1 trillion in context, the entire national defense budget is less than $1 trillion, and today’s interest expense amounts to half of discretionary spending after mandatory expenses are paid, such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. When nearly three-quarters of the government’s budget is mandatory spending (combining mandated social benefits, other mandated spending and current interest expenses), it is a difficult challenge to find the savings to help lower the debt burden or balance the budget.

The tax bill currently being debated in Congress could see significant changes, but its final form is highly likely to deepen the budget deficit. While the current proposal includes select spending cuts, it reduces revenue by lowering taxes and increases net spending, notably by expanding the defense budget. While final figures will only be available after the tax bill is approved, the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates it will add $2.4 trillion to the deficit over the next 10 years. But the impact could be higher insofar as many of the proposed tax cuts are scheduled to sunset over the next 10 years, mathematically lowering the long-term impact of tax cuts on the budget. But history shows that Congress is highly unlikely to allow tax cuts to end, as to do so would be effectively voting for tax increases. According to the CBO, if none of the sunsetting tax cuts are allowed to expire, the tax bill would add $3.8 trillion to the deficit, nearly 10% of the current outstanding total government debt.

A significant unknown in estimating the current budget is the revenue that could be gained through tariffs. Tariffs could raise a meaningful amount of money to lower the deficit, but they also could dampen economic growth and increase inflation at least temporarily, leading to higher rates. These impacts in turn could in turn dampen tax revenue, offsetting some of the benefits of tariff revenue.

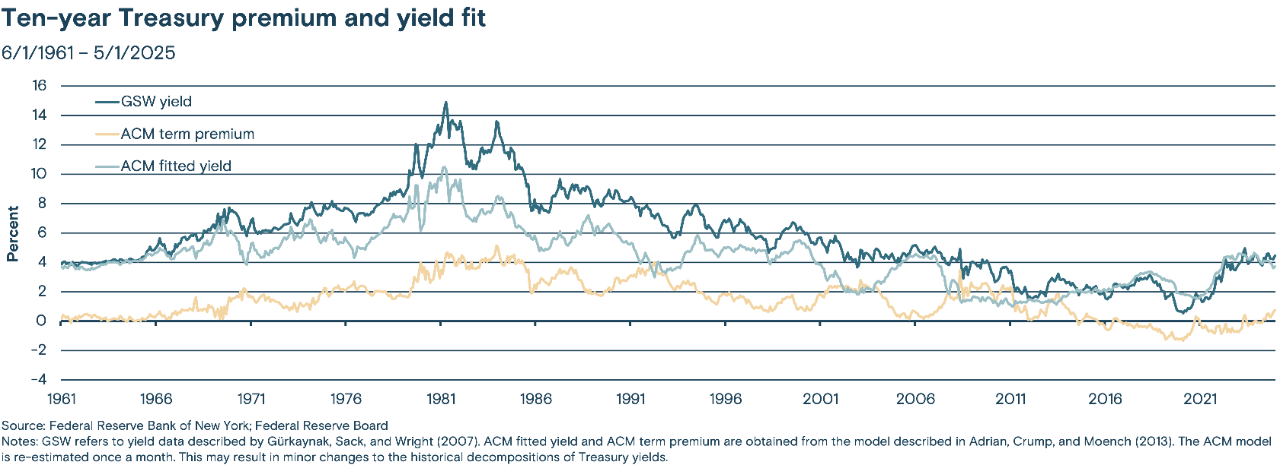

When lending to the U.S. government, investors can choose between short-term lending via short-maturity Treasury securities, like T-bills, or longer-term lending via 10-year Treasury notes or 30-year Treasury bonds. Typically, longer maturity loans offer greater yields, in part to compensate for the compounding effect that could be achieved by buying a series of shorter-term loans, and in part for the greater uncertainty involved in lending money for long periods of time. The latter is referred to as the “term premium”—the yield premium received for taking longer-term risk.

The term premium in benchmark 10-year Treasuries, as can be seen in the chart below, has been steadily rising since 2020 when the term premium was negative—largely due to high demand for safe-haven securities like benchmark Treasuries, but also steady buying by the Federal Reserve (Fed). This rise in the term premium has been in part due to concerns about inflation, and more recently due to concerns about worsening debt dynamics, the commitment of foreign buyers of Treasury bonds and uncertainty over economic policy. The key issue with higher term premiums is they raise the cost of issuing debt, which then can feed back into worsening debt dynamics.

Meanwhile, credit default swaps (CDS), a derivative security which measures the probability of a bond defaulting, currently price the risk of the U.S. government defaulting on its debt at a similar level to Italy (rated BBB+), a country where structural debt problems have long been an issue, and even Greece (rated BBB-)—where financial mismanagement sparked the 2011 European financial crisis. Using CDS as a measure of confidence in fiscal management, current levels place confidence in the U.S. below the United Kingdom (rated AA), France (Aa3) and Spain (A)—all countries with lower credit ratings.

To be clear, the probability of default these CDS spreads signal is very low, and we see no reason to believe the U.S. government will chose to default—it would have to be a choice as the debt is not in a foreign currency but in U.S. dollars, meaning the Treasury could always print more money to pay back the debt, despite this being inflationary and likely raising interest rates further. But in today’s more uncertain environment, the market is making a point by pricing a lower risk of default for American companies like Apple (rated AA+), and Microsoft (one of the few AAA-rated companies), than for the U.S. government.

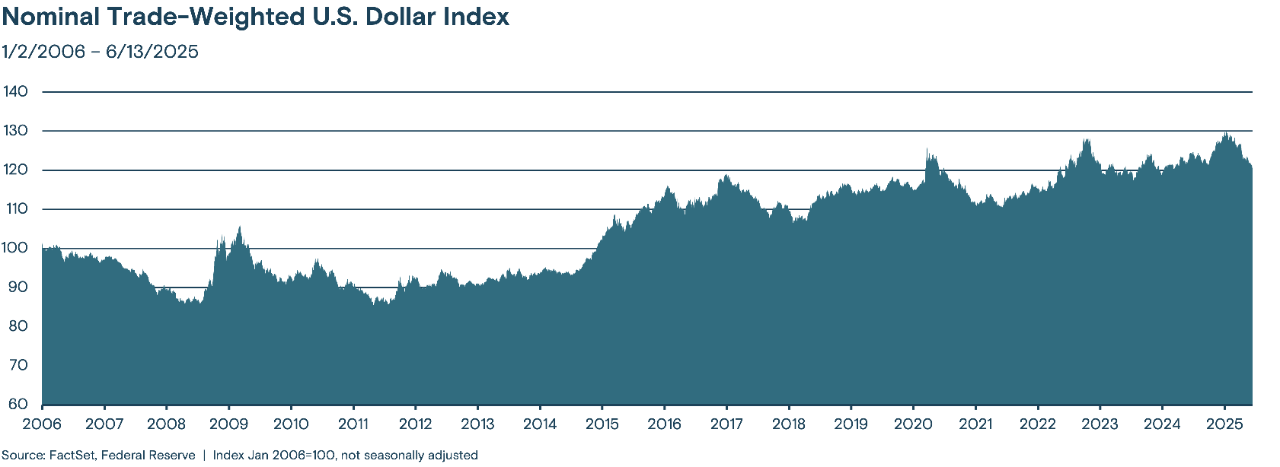

Finally, the U.S. dollar has been steadily weakening since the start of the year. While currencies are influenced by a multitude of factors, the strength of the U.S. dollar has waned while Treasury yields have risen, which is usually supportive for a currency. This divergence between the direction of yields and the U.S. dollar suggests its recent weakness is largely due to growing concerns about owning U.S. assets given uncertain economic policy and the country’s deteriorating fiscal position.

While the U.S. dollar has only weakened back to late-2024 levels, the U.S. is substantially dependent on foreign demand for Treasury securities. Currently, foreigners own around 30% of the total stock of outstanding Treasuries, and U.S. dollar strength is partly dependent on a steady demand for purchasing U.S. assets. As such, a weakening U.S. dollar could be both an effect of deteriorating sentiment and a cause of it. Should foreigners, who have shown some signs of diversifying into gold or Japanese government bonds (especially now that yields have risen in Japan) slow their purchase of Treasuries, the U.S. dollar could weaken further, fueling a vicious circle.

The current administration has been consistent in its view that the preferred solution to decreasing the annual budget deficit and ultimately lowering the total stock of debt is to accelerate economic growth, boosting revenues. In its view, this can be successfully accomplished with a combination of lower tax burdens, deregulation, investment incentives and a trend toward onshoring, supported by higher tariffs. While we don’t doubt the broad economy can benefit from many of these actions, the extent and magnitude of these benefits, and the time horizon required to realize them, are not clear.

An alternative approach is for the executive and legislative branches to focus on aggressive spending cuts. While this is also a priority of the current administration, Congress is notoriously reluctant to cut spending insofar as it can directly or indirectly affect constituents. This is true not only of the largest social programs that make up the bulk of the federal budget, but of the smaller discretionary items that are already being squeezed by the mandatory programs.

A more technical and possibly controversial approach would be the direct suppression of longer-dated interest rates by the Fed. There is a precedent for this as the Fed was an aggressive buyer of Treasury securities after both the GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic with the explicit intention of keeping interest costs low, reducing the cost of financing for the government, corporations and consumers through lower mortgage rates.

Market perspectives delivered direct to your inbox

Subscribe to timely and relevant news, information, and trends on the topics that interest you most.

Given the time it could take for economic growth to rebound sufficiently to help reduce the deficit, and the political and logistic challenges of the alternative approaches to reducing government debt, the most likely outcome should sentiment continue to wane, is that the bond market forces the government to take action. Historically, burgeoning debt levels can persist for years and then suddenly hit a tipping point and matter a lot, sparking a surge in interest rates and sometimes a crisis.

The United Kingdom is a recent example that comes to mind. In 2022, when the country’s debt load was already stretched, Prime Minister Liz Truss proposed a budget with unfunded tax cuts. Lacking the confidence that such a plan would succeed in creating sufficient economic growth to eventually fund the tax cuts, the bond market revolted. Aggressive selling of gilts (the common name for U.K. government bonds and shorthand for “gilt-edged security” as the British government has never missed an interest or principal payment on its debt) pushed interest rates rapidly higher. As higher rates put further pressure on the government’s borrowing costs, the fiscal outlook further deteriorated, prompting more selling. Ultimately the Bank of England was forced to intervene, buying gilts from the market, and the prime minister resigned.

In our view, a similar scenario could unfold in the U.S. if the fiscal outlook continues to deteriorate. Domestic and foreign bond investors could accrue sufficient conviction in their concerns to begin a cycle of selling that requires an immediate and aggressive governmental response. And like in the U.K., once confidence has collapsed, it takes substantial and meaningful change to earn that confidence back.

Such a scenario is not our base case, or a view that is influencing our current strategic asset allocations. But we are mindful that the recent increases in risk premiums and CDS spreads, together with a weaker U.S. dollar, are signals that the bond markets are becoming increasingly concerned about the sustainability of the U.S. government’s approach to debt.

In the meantime, we expect Treasury bonds will remain responsive to changes in the outlook for the economy and the path of inflation. The budget, the impact of tariffs on growth and inflation as well as geopolitics will remain the most important drivers of U.S. government bond yields in the months ahead. And we have great faith in the U.S. economy’s ability to adapt to challenges and shocks.

Media contact: Callie Briese, 612-844-7340; callie.briese@thrivent.com

All information and representations herein are as of 06/24/2025, unless otherwise noted.

The views expressed are as of the date given, may change as market or other conditions change, and may differ from views expressed by other Thrivent Asset Management, LLC associates. Actual investment decisions made by Thrivent Asset Management, LLC will not necessarily reflect the views expressed. This information should not be considered investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or product. Investment decisions should always be made based on an investor's specific financial needs, objectives, goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance.

This article refers to specific securities which Thrivent Mutual Funds may own. A complete listing of the holdings for each of the Thrivent Mutual Funds is available on thriventfunds.com.

The Nominal Trade-weighted U.S. Dollar Index measures the value of the U.S. dollar based on its competitiveness versus trading partners.

Any indexes shown are unmanaged and do not reflect the typical costs of investing. Investors cannot invest directly in an index.

Yields on Treasury securities are composed of two components: expectations of the future path of short-term Treasury yields and the Treasury term premium. The term premium is defined as the compensation that investors require for bearing the risk that interest rates may change over the life of the bond. Since the term premium is not directly observable, it must be estimated, most often from financial and macroeconomic variables. The Adrian, Crump, and Moench (ACM) model provides an approach for extracting term premiums from Treasury yields.

Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results.