Employment has weakened

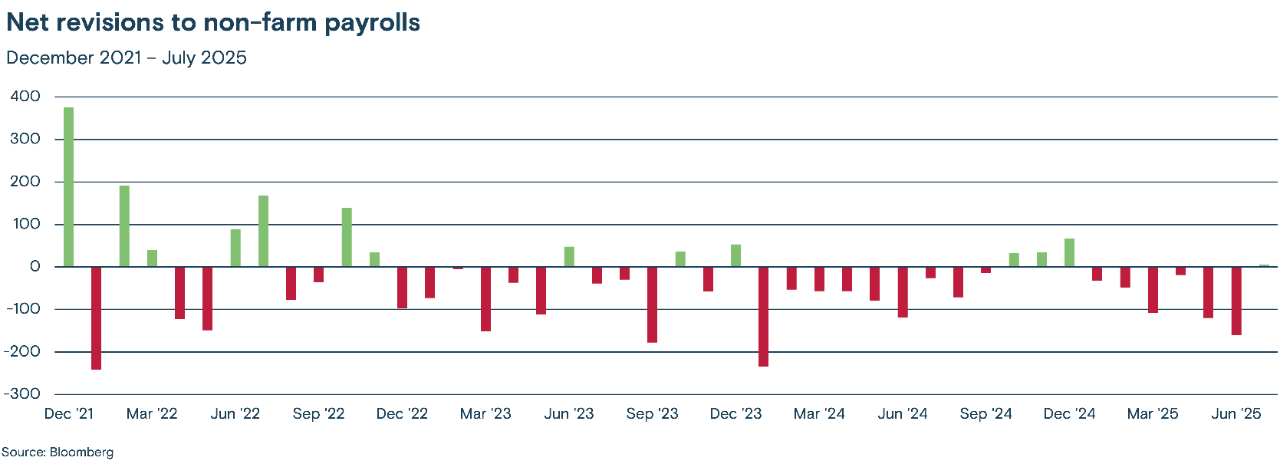

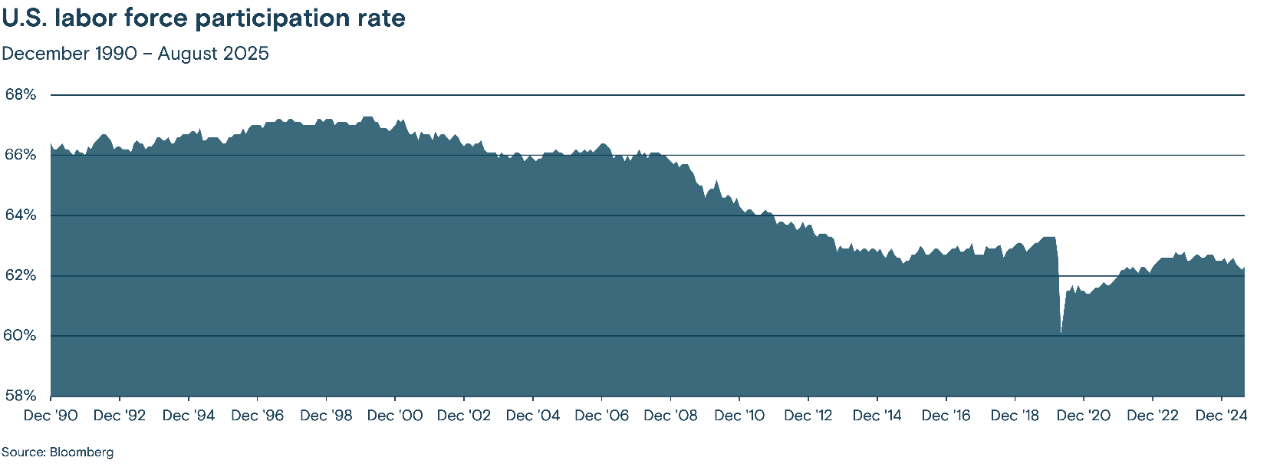

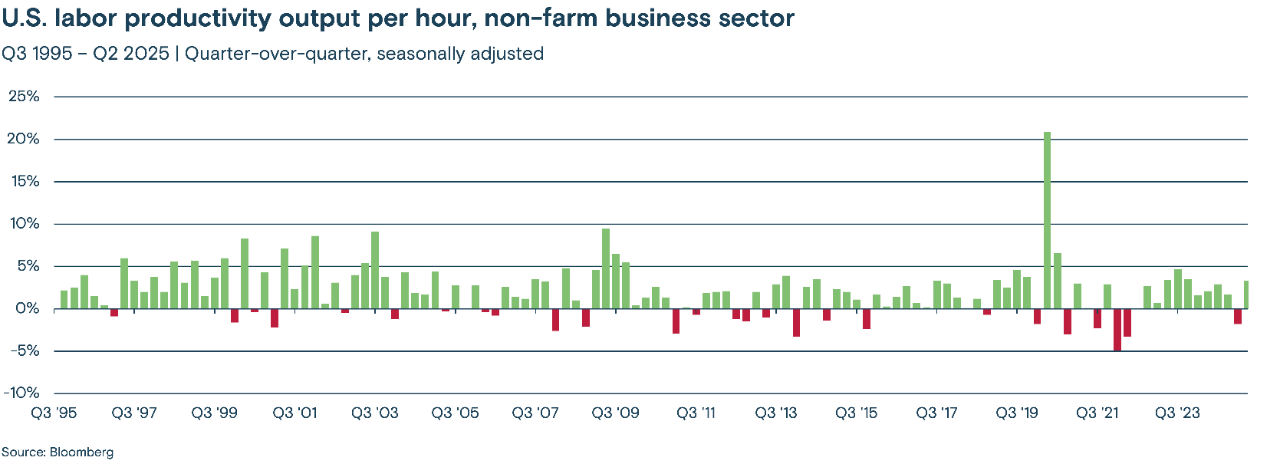

Recent BLS data has pointed to a significant decline in new jobs, and a broad and detailed analysis of the various data sources backs this up. Employment is weakening, and the latest annual revisions in jobs created suggest it has been weaker than expected, and weaker for longer than the market assumed. Finally, recent data has shown that the strength in the jobs market has been relatively narrow. Government and government-adjacent industries have accounted for a significant portion of the new jobs created, while employment in manufacturing and other goods-producing sectors has been weak. More recently, simply excluding health care (a relatively non-cyclical sector) and social assistance programs, net employment has been negative.

The broadest measure of unemployment, which includes unemployed people and people only working part-time, has risen steadily since the summer of 2023, and confidence in being able to find a job has been declining. A recent New York Fed survey asking those currently employed how confident they were about finding a new job in the next three months fell to its lowest reading since the survey began in 2013, and various data series suggest their pessimism may be justified. Job postings at Indeed.com are down, and the most recent Challenger Survey’s total of job hiring announcements was its lowest since 2009. Today, the sum of people employed plus the number of current job openings is fewer than the total labor force. That is, if layoffs continued at their normal pace, new jobs created would likely turn negative.

But not every indicator is weak or negative. The latest NIFB’s Small Business Hiring Plans Index shows that smaller businesses are increasing hiring, while business confidence broadly has shown signs of recovering after dipping during the height of the tariff policy uncertainty. And the JOLTS survey has shown companies may not be hiring, but are reluctant to fire, presumably anticipating a better economic environment in the quarters ahead.

In our analysis, the jobs market has softened as a result of relatively typical layoff rates combined with a reluctance to hire. Such an environment could persist in the months ahead and find support in lower interest rates, lower taxes, successful adaptation to new tariffs and a generally more favorable regulatory environment. But should the rate of layoffs start to rise, the risk of a spiraling jobs market will accelerate.

The data is in the details

Headlines rarely tell the whole story, and economic data releases are no different. When it comes to employment data, the need for thorough analysis and rigorous debate is even higher, given larger revisions, changes in the labor force, one-off factors that distort the data and the impact of AI.

Furthermore, we expect markets will continue to see initial job estimates from the BLS as being more reliable than they are. For example, estimates for changes in future interest rates have been particularly volatile around jobs reports that significantly exceeded or underperformed expectations, even if the reported number was within the BLS’s estimate of its margin of error.

As we navigate the current economic environment, we encourage investors to be mindful that data releases generally are more volatile during turning points, especially when transitioning from a relatively stable jobs market to a weaker one. And we encourage investors to keep in mind that all economic data, including gross domestic product (GDP), is subject to revision. A healthy skepticism should be applied to all headlines reporting initial estimates, and confidence should be placed in trends visible only after collating all of the available data and considering the context.