Tariffs are here to stay

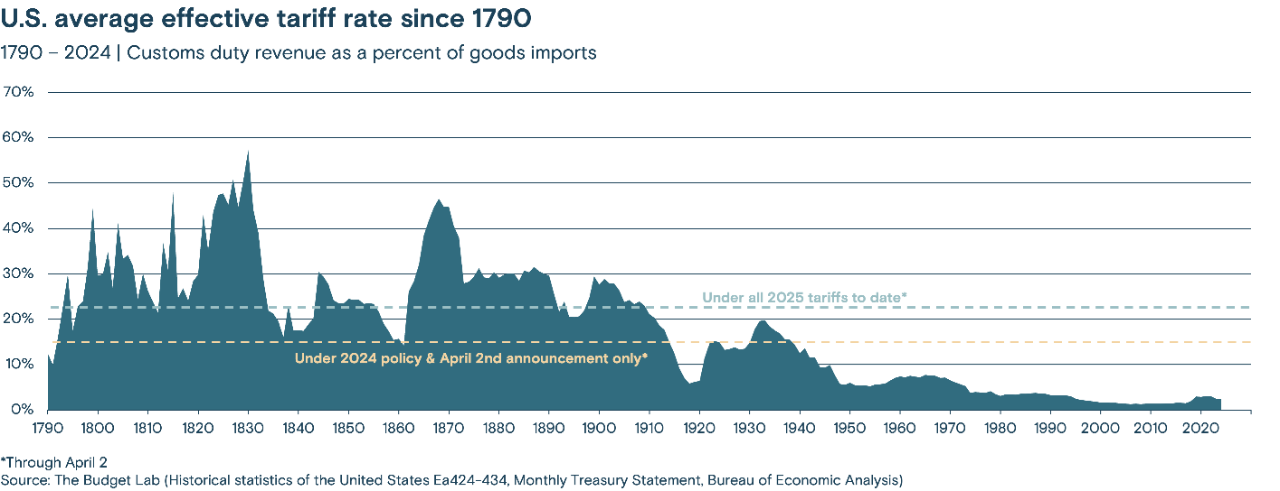

Higher tariffs are likely to be a fact of economic life, at levels high enough to put both downward pressure on economic growth and upward pressure on inflation. The U.S. administration believes the terms of trade have been unbalanced, and that tariffs are a key tool to reorder trade. U.S. tariffs on imports generally are lower than those of trading partners.

The use of tariffs and other tools are intended in part to onshore more production of goods in the U.S. In particular, the administration believes it can rebuild manufacturing jobs in the U.S., which have fallen roughly 35% from peak levels in the late 1970s1. As imports have risen, core inflation has fallen over the past 30 years, outside of the COVID-19 surge. That’s the tradeoff that the U.S. essentially made—more imports and less manufacturing jobs for lower prices.

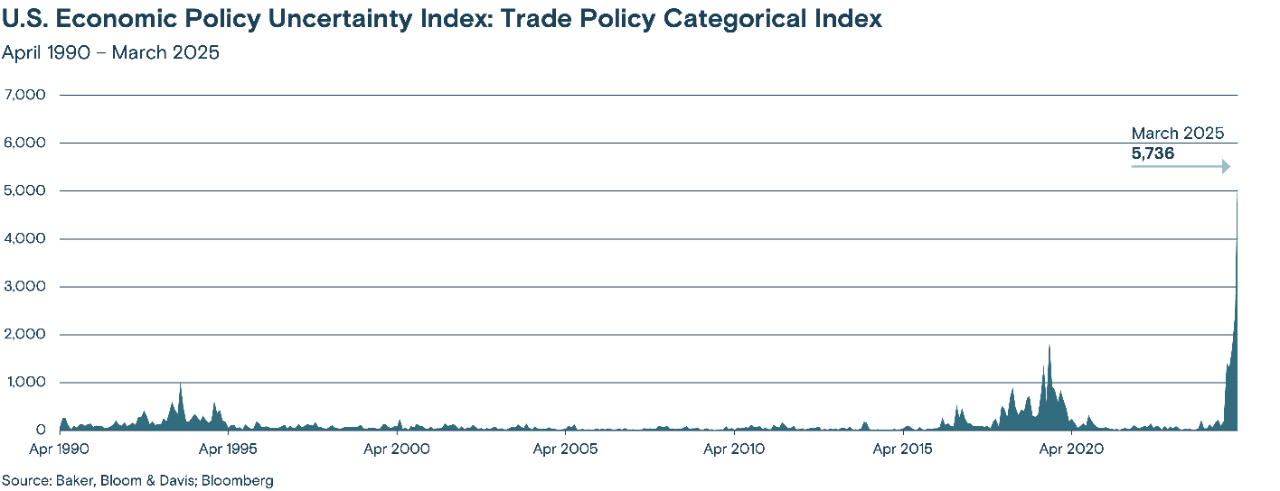

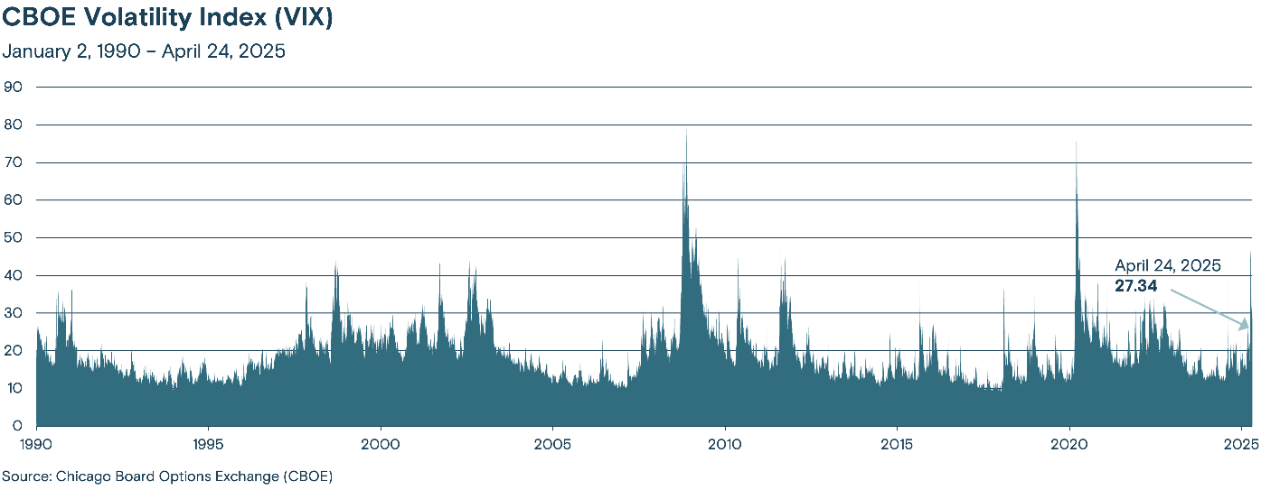

While market volatility has prompted the administration to delay or lower tariff levels, we expect the White House will persist until satisfactory deals are reached—deals which likely will include higher tariffs than the economy has seen in decades.

Slowing economic growth…

Because of the direct and indirect impact from tariffs, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in April lowered its growth forecast for the U.S. in 2025 to 1.8% from 2.7%. The 0.9% decline in growth is less than consensus expectations, which is probably closer to a 1.5% decline (estimates vary widely and are highly dependent on the level at which tariffs stabilize). But it is not just the U.S. that will slow under higher tariffs. The IMF cut its forecast for global trade growth almost in half, from 3.8% last year to 1.7% this year, and cut its estimate for 2025 global economic growth from 3.3% to 2.8%, the slowest growth rate since 2020 (when the pandemic shocked global trade), and the second-worst global growth rate since the 2008 financial crisis.

If the good news is that forecasted annual growth rates generally are still positive (keeping in mind that a recession requires two consecutive quarters of negative growth), a key concern is that growth can rapidly decelerate. Slower growth can beget slower growth, as one company’s cutbacks impact other companies, which then cut back and so on. While growth in the first quarter has shown signs of weakness, it has also shown signs of strength, particularly in employment.

Consumer and business confidence has fallen as a result of high uncertainty. Consumers, however, so far have kept spending, as how consumers feel and what they do can vary. The labor market remains solid, which creates income for people to spend. Whether this holds up if prices start rising is a key question.

More concerning is the fall in company confidence, and in particular confidence of CEOs. Again, the key issue is uncertainty as the policy backdrop keeps shifting, sometimes within a day. It’s hard for a CEO to plan ahead and make investments in this environment. On recent earnings conference calls, companies have been tepid about their outlook, the most since the Global Financial Crisis.

If a lack of consumer confidence eventually results in a sharp decline in consumption, or dwindling business confidence begins to affect the labor market, then we could be increasingly closer to an economic tipping point.

…And raising the risk of higher inflation

Tariffs likely will push up prices, but we do not expect it will be large enough or last long enough to push inflation into a vicious cycle, such as seen in the inflation-ridden 1970s and early 1980s. However, like economic growth, inflation can turn rapidly, threatening a trend toward higher rates, particularly if expectations for future inflation become embedded. On the other hand, if the uncertainty around tariffs subsides, and both consumers and businesses can plan around a short-term bump in prices, the inflationary impact from tariffs could ultimately prove temporary.

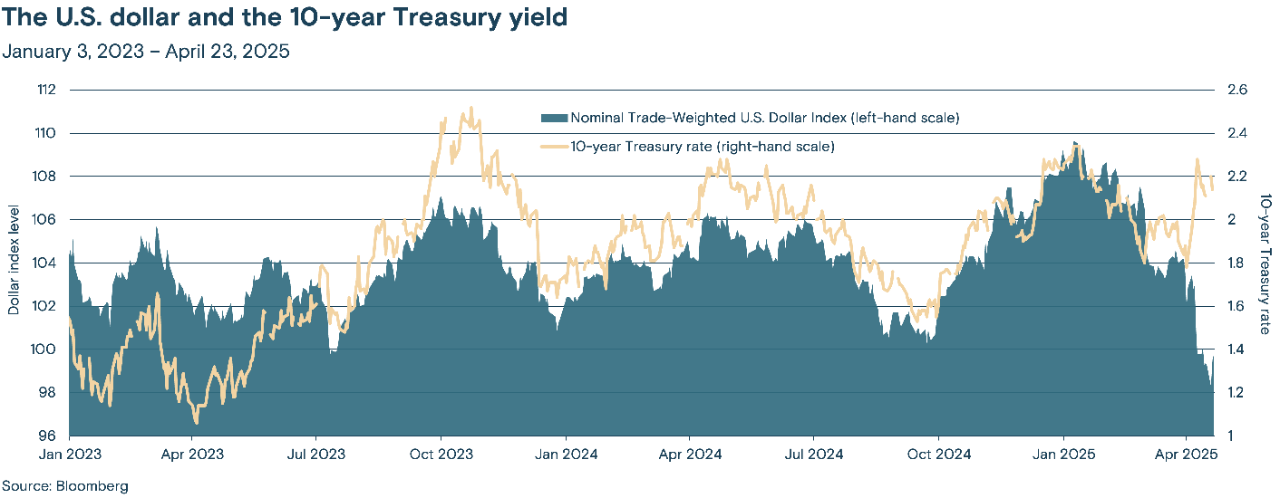

The Fed will wait for clarity

Recent comments from Fed Chairman Jerome Powell have indicated the Fed has little additional clarity and conviction about the path of growth and inflation than the market does. As such, the Fed is likely to neither raise nor lower interest rates until the economic and inflation data forces its hand. Our view remains that the Fed is more likely to cut rather than hike rates on the assumption that tariffs are likely to put temporary pressure on inflation, and a slowing economy would benefit from lower rates with little risk of overheating.